Background

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of infectious diseases that affect approximately 1.5 billion people globally. Often rooted in poverty, these illnesses present serious risks to health and well-being, particularly in low-income communities. Nigeria is the most affected country in sub-Saharan Africa, shouldering 25% of the region’s NTD burden, with over 122 million individuals at risk of multiple NTDs. Among the five prioritized NTDs targeted for elimination through preventative chemotherapy (PC)—including lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, soil-transmitted helminthiasis, schistosomiasis, and trachoma—the World Health Organization (WHO) advocates for annual or bi-annual mass drug administration (MDA).

In alignment with WHO’s 2030 Road Map for NTDs, Nigeria aims to eliminate these PC-NTDs by 2030, with a focus on improving MDA coverage as stated in its national health policy. The Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) oversees MDA implementation in collaboration with various non-governmental development organizations (NGDOs). One prominent partner, Sightsavers, has worked alongside the FMoH since 1953, helping deliver over 590 million PC-NTD treatments across seven Nigerian states.

MDAs for lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis are conducted at the community level, where health workers distribute medications to all involved residents. In contrast, treatments for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis primarily target school-aged children, with campaigns conducted in households or schools.

Since its introduction in 2010, Nigeria has utilized the DHIS2 (District Health Information Software 2) to manage health data, which covers various diseases, including polio, malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS. Traditionally, data on PC-NTD MDAs were collected through manual paperwork, where community drug distributors recorded treatments, necessitating multiple summary sheets that were later digitized. This method, while adequate at the community level, suffers from delays in data reporting and quality concerns, a challenge common in several countries such as Ghana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan.

In Nigeria, the reliance on this outdated paper-based system—combined with the complexity of collaboration among various partners—has led to data inconsistencies and fragmentation, which in turn impedes timely reporting and comprehensive data availability during and post-MDA campaigns. Key issues include challenges in tracking drug inventories and assessing campaign progress due to the lack of centralized data storage.

Development and Implementation of a New Platform

Between 2019 and 2021, the FMoH, in partnership with Sightsavers, developed a new electronic data collection platform designed to replace the previous system reliant on spreadsheets. Drawing from a similar initiative in Zimbabwe, this DHIS2-based platform allows for real-time monitoring and data access during MDAs. Its introduction aimed to centralize historical and ongoing treatment data while facilitating programmatic adjustments during campaigns.

This article provides an overview of the pilot project and the initial scaling phases of this new platform across various MDA scenarios in Nigeria. Key objectives included:

– Assessing the platform’s capability to deliver timely and high-quality data across diverse contexts.

– Identifying the potential for using this data to drive programmatic actions.

– Evaluating its effect on government ownership of the data.

– Recognizing barriers and enablers that could influence ongoing implementation.

Insights and Challenges

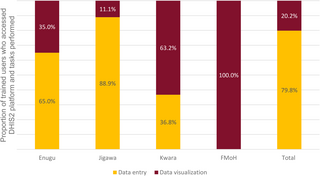

Significant overlaps were observed between data ownership components (access, control, and use) and core research questions. Analysis indicated that state and local government actors could access and utilize the platform’s data in real-time, contrasting sharply with previous MDAs, where data access was restricted until after the campaigns concluded. This advancement underscores the transformative potential of the DHIS2 platform in improving data accessibility, consistent with findings from other healthcare contexts.

However, participants noted that internet accessibility remained a significant hurdle in successful platform implementation. Issues similar to challenges faced in Bangladesh and Kenya, such as connectivity and cost, became critical to the platform’s effectiveness. These technical and infrastructural barriers must be carefully addressed in future scale-up planning to ensure optimal data quality.

A positive correlation emerged between data access and quality; participants reported that the DHIS2 dashboard facilitated better monitoring of MDA data, allowing them to catch and correct errors promptly. Instances of perceived data manipulation were flagged by state-level users, highlighting the platform’s role in fostering accountability and enhancing data integrity.

Despite improvements, discrepancies in treatment coverage estimates between the DHIS2 system and external surveys revealed weaknesses; some findings deviated significantly from expected norms. This discrepancy emphasizes the need for program managers to compare data from multiple sources before making planning decisions.

The participants consistently highlighted several practical applications for the data from the DHIS2 platform, particularly in tracking MDA performance, planning future activities, and informing strategic choices. This newfound capacity to harness data in real-time fostered a sense of optimism among stakeholders, enhancing collaboration and efficient inventory management.

Overall, there was a noticeable improvement in perceived data ownership, which participants attributed to the structured data access provided by the DHIS2 platform. This system has empowered MDA teams and encouraged swift responses to emerging issues. The enthusiasm for scaling the system at the Federal level reflects its potential, albeit with challenges related to workload, capacity building, and connectivity that need addressing.

As Nigeria looks to broaden the platform’s use, the FMoH must recognize the varied contexts in which NGDO partners operate and the differing challenges they face. Crafting a one-size-fits-all approach may not yield the desired results; further research across diverse settings could enhance understanding and implementation of this innovative tool. Stakeholders are encouraged to consider various factors when scaling up and improving data ownership, access, and quality in future NTD campaigns.