For centuries, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has utilized tongue examinations as a diagnostic tool, analyzing its color, shape, and coating to identify health conditions. Recent research has prompted scholars to explore how this age-old practice can be integrated with modern artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, leveraging studies that demonstrate links between tongue color and health.

TCM has often stirred debate within the global scientific community. In 2022, the World Health Organization recognized TCM diagnoses by incorporating them into the International Classification of Diseases, a globally accepted health information framework. However, significant skepticism persists. “Despite the expanding TCM usage and the recognition of its therapeutic benefits worldwide, the lack of robust evidence from the EBM [evidence-based medicine] perspective is hindering acceptance of TCM by the Western medicine community and its integration into mainstream healthcare,” noted authors of a review article published in 2015. Still, academic interest in TCM endures.

According to Dong Xu, a researcher at the University of Missouri focusing on computational biology, tongue color is a crucial indicator of the body’s blood and qi—often termed ‘vital energy’ in English. He co-authored a 2022 study that analyzed digital images of tongues. However, the subjective nature of tongue examination, heavily reliant on a practitioner’s perception, complicates its reliability.

Frank Scannapieco, a periodontist and microbiologist at the University at Buffalo, explains that Western medicine lacks standardized methods for assessing tongue features, although certain tongue lesions can indicate diseases like cancer. Elizabeth Alpert, a dental health expert with affiliations at Harvard School of Dental Medicine, emphasizes that while tongue examinations are part of oral cancer screenings conducted by dentists, their effectiveness depends on the provider’s skill and experience.

Recent advancements in computing technology have spurred TCM-inspired medical researchers to reevaluate tongue diagnostics. In a 2024 study published in Technologies, researchers applied machine learning to categorize tongue colors and link them to various health conditions, boasting an impressive accuracy of 96.6%.

Previously, studies faced challenges due to perception biases caused by fluctuating light conditions, according to Javaan Chahl, a roboticist and co-author of the recent study. “There have been studies where people tried to [diagnose via tongue color] without a controlled lighting environment, but the color is very subjective,” Chahl remarked. To mitigate this, his team designed a controlled lighting system housed in a kiosk. This setup required patients to place their heads inside a chamber illuminated by stable LED lights while exposing their tongues.

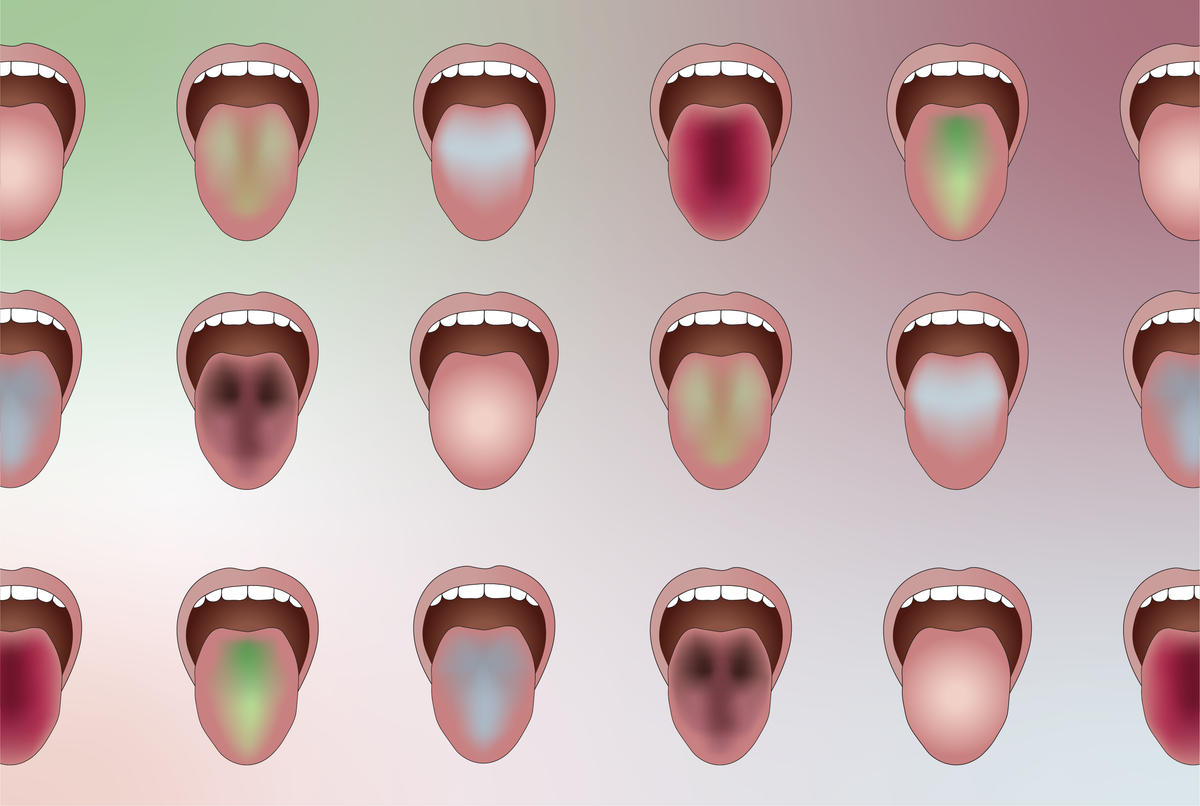

From this setup, researchers captured a dataset of 5,260 images, combining real photographs and gradient images of tongues. Using this data, they taught machine-learning algorithms to recognize seven distinct tongue colors—red, yellow, green, blue, gray, white, and pink—across various light conditions.

Their findings revealed that a healthy tongue appears predominantly pink with a thin white film, while a white tongue could indicate iron deficiency. Patients with diabetes often present bluish-yellow tongue coatings, and a purple tongue with a thick fatty layer may point to certain cancers. Notably, the intensity of COVID-19 infections was linked to tongue color, with a faint pink hue observed in mild cases, crimson in moderate cases, and deep red in severe situations.

The researchers then applied their most accurate machine-learning model to assess 60 tongue images, gathered with the standardized kiosk setup at two Iraqi hospitals in 2022 and 2023. The comparisons with patients’ medical records showed a high success rate, as study co-author Ali Al-Naji confirmed, stating, “The system correctly identified 58 out of 60 images.”

Currently, Al-Naji aims to fine-tune diagnoses by concentrating on specific areas of the tongue. Additionally, his team seeks to analyze a new dataset of 750 internet images to study tongue shapes and oral conditions like ulcers using advanced deep-learning algorithms.

While Xu notes the potential of tongue color as a biological marker for health, he cautions against relying solely on this method for clinical decisions. He asserts, “the most fundamental limitation of current tongue-imaging systems is that tongue analysis represents only one component of a complete TCM diagnosis,” which is compounded by a lack of standardized image labeling.

Chahl acknowledges a growing commercial interest in their system but emphasizes that the primary barrier remains the collection of useful data. Conducting broad-scale research requires the involvement of numerous participants to gather diverse images and consent to access their medical histories.

Scannapieco highlights the complexities of establishing standardized tongue assessments within clinical or research environments, asserting that significant investments in databases and image collections are essential for widespread AI integration. He predicts, “Until then, I think the field will develop by accretion of small studies that reveal correlations between tongue appearance and specific conditions.”

In the meantime, AI platforms for tongue analysis have quietly gained traction among consumers. Earlier this year, Xu and his team rolled out a GPT-based application named BenCao, allowing users to upload tongue images for personalized health insights based on TCM principles.

Currently marketed only as a “wellness” tool rather than a formal diagnostic application, the app provides lifestyle and dietary recommendations. “We provide only some food and lifestyle recommendations,” clarified Jiacheng Xie, Xu’s Ph.D. student. To enhance its clinical application, they aspire to collaborate with healthcare providers, comparing machine-learning outcomes with those of human practitioners to identify disparities and improve overall performance.